By Andrew Iida I Head Writer and Resident EMT

The early 1970’s was a bleak time for marine mammals.

The public had grown increasingly aware that because of human activity, many species were headed towards a certain extinction. The populations of some of our favorite animals in La Jolla, including the California sea lion and the gray whale, were steadily declining and the country began to realize that without taking action, they could be lost forever. With mounting public pressure, politicians took action.

The text of the House of Representatives shows us just how serious the problem was. A report from the Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries in 1971 states, “Recent history indicates that man’s impact upon marine mammals has ranged from what might be termed malign neglect to virtual genocide”.

Fortunately, we still had a functioning government in 1972 (the Watergate scandal was just about to erupt the following year), and Congress passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act in a near-unanimous vote. The act was signed into law in October of the same year by President Nixon, and took effect in December.

The act begins by explaining what Congress found during the hearings, and why those findings necessitated new laws. They found that human actions were threatening to drive marine mammals to extinction, and action needed to be taken to keep these animals at a sustainable population level. Additionally, human intervention was needed to replenish the populations of animals that had dropped below that level. They argued that such actions were necessary because marine mammals are important to the world, not just because of their recreational and economic value, but also because of their aesthetic significance.

When the act was signed into law, it became illegal to import, export, or sell any marine mammal, animal part, or animal product, and established the Marine Mammal Commission as an independent oversight agency. More significantly, it outlawed the “take” of any marine mammal, which it defines as “the act of hunting, killing, capture, and/or harassment of any marine mammal; or, the attempt at such.” Any individual who is seen touching, feeding, or otherwise harming marine mammals can be fined up to $100,000 and imprisoned for one year.

After nearly 5 decades of protection, the MMPA has been a huge success. The gray whale population is steadily rising, the number of California sea lions has tripled, and not a single marine mammal has gone extinct in the United States since it was passed. Unfortunately, the rest of the world was slower to catch up to our environmental protection standards, and the Japanese sea lion was hunted to extinction. Despite its success, there are people who oppose the MMPA, and President Trump’s proposed budgets for both 2018 and 2019 completely eliminated funding for the Marine Mammal Commission. Fortunately, the agency still exists, but it has us worried. We don’t think that one penny a year from each American is too high of a price to pay.

At Everyday California, we’re passionate about ocean conservation and environmental protection, which is why we’ve partnered with 1% for the Planet to donate a portion of every purchase to GreenWave; a nonprofit working to mitigate the harmful effects of climate change via sustainable underwater farming. We take the MMPA very seriously, and we hope it continues to be an effective defender of our planet. We understand that we have a huge responsibility to keep our oceans clean and our animals safe, so we always follow the NOAA guidelines for whale watching by staying 100 yards away from the whales, and if they approach us, we never feed them, touch them, or go between two whales.

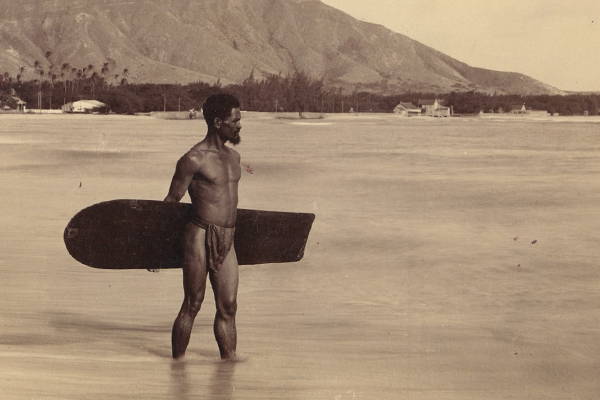

Our commitment to the planet is also the reason we choose kayaks instead of boats with motors on our whale watching tours. While riding in a powerboat might be easier than kayaking, the convenience to humans is offset by the harm that it causes to the ocean. In addition to the increased carbon emission from the boat’s fuel use and the potential for a spill of fuel or oil, whale watching tours on motorized boats are hazardous to the very animals that they depend upon. The International Whaling Commission maintains a database of ship strikes and has found that whales are more likely to be struck by a whale watching boat than any other type of ocean vessel. A ship strike can be fatal to both the passengers and the whales, who have no protection from the propeller blades.

The gray whales that we see on our tours are especially vulnerable. They pass by La Jolla each winter during their annual migration to Mexico, where they mate and give birth to their calves. If we harass them, we might disrupt their feeding, rest, or mating, and we would risk threatening the entire population. Noise pollution is a huge threat to gray whales, and the sound of boat engines can alter their behavior, hindering their ability to survive and thrive. Kayaks are cleaner, safer, and provide a more intimate and better overall experience for us and the whales.